Too many buyers choose the wrong stop valve. The result? Leaks, complaints, and replacement costs.

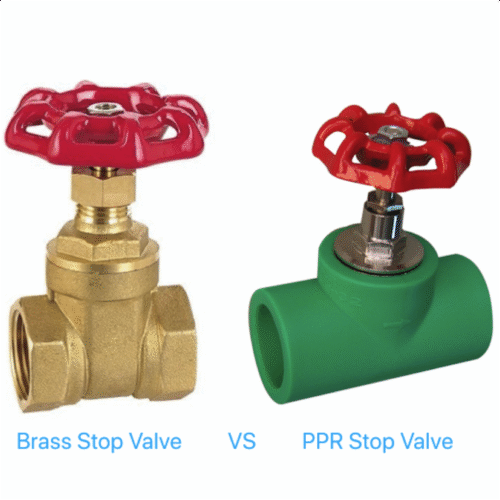

PPR stop valve and brass stop valve serve similar functions, but they differ in material, performance, and ideal applications. Let’s break down which is right for your needs.

If you’ve ever struggled to choose between a plastic or brass valve, you're not alone. I’ve seen buyers regret their decision after discovering the limits of the wrong material. But don't worry — in this article, I’ll help you understand the differences clearly so you can make the best choice next time.

What is a PPR Stop Valve?

PPR Stop Valve Plumbing

Many buyers think plastic valves mean low quality. That’s not always true. It depends on where and how you use them.

A PPR stop valve is a plastic valve made from polypropylene random copolymer (PPR), designed to control or stop the water flow in plumbing systems.

PPR (Polypropylene Random Copolymer1) is a thermoplastic material often used in residential and commercial plumbing, especially in hot and cold water systems. A PPR stop valve is commonly installed before faucets or toilets to allow maintenance without shutting off the main supply.

Key Features of PPR Stop Valves:

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Material | Plastic (PPR) |

| Resistance | Corrosion-resistant, no rust |

| Weight | Lightweight |

| Cost | Lower than brass |

| Welding Method | Heat fusion (no threading or sealing tape) |

| Temperature Range | Up to 95°C (203°F) |

| Common Applications | Residential bathrooms, kitchens, hot/cold water systems |

Why use PPR stop valves?

PPR valves are mostly used in projects where the whole system uses PPR pipes. They offer smooth inner surfaces, so they don’t collect scale or rust. This is important for long-term hygiene and water quality. Also, since they’re plastic, they don’t react chemically with water, which means fewer chances of pipe corrosion.

That said, their strength is also their weakness. They’re not ideal for high-pressure or exposed environments where external impacts might occur. If you're dealing with commercial or industrial systems, brass might serve you better.

What is the Purpose of a Stop Valve?

Stop Valve Function

Sometimes clients ask me, “Why not just use the main valve?” I explain — replacing a faucet shouldn’t mean shutting water off for the whole building.

A stop valve allows localized control over water flow, making maintenance and emergency shut-offs easier without disrupting the entire system.

They’re most often installed near toilets, sinks, water heaters, or appliances. This allows maintenance without turning off the main water supply. It’s also useful during emergencies like leaks or burst pipes.

Common Use Cases for Stop Valves:

| Location | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Under sink | Easy faucet replacement or maintenance |

| Toilet line | Shut off water during repair or overflow |

| Water heater | Control flow without main supply disruption |

| Washing machine | Isolate the unit for maintenance |

Why stop valves matter to installers and end users:

From a technical perspective, stop valves help isolate parts of a plumbing system. From a business angle, they save time and labor. A single stuck valve can delay an entire job. That’s why my team always recommends clients to double-check the quality and function of every stop valve before installation.

If your project is residential, small repairs without disrupting daily use are a key selling point. In large commercial buildings, localized shutoff becomes critical during emergency maintenance. So choosing the right type of stop valve is not a small decision — it directly affects the reliability of the whole plumbing system.

PPR Stop Valve VS. Brass Stop Valve, What's the difference?

Brass vs Plastic Stop Valve Comparison

Both control water, both stop flow — but only one fits your project needs.

PPR stop valves are lightweight, corrosion-resistant, and ideal for low to moderate pressure systems, while brass stop valves offer superior strength, pressure resistance, and longevity.

Let’s look deeper at their differences:

Comparison Table

| Feature | PPR Stop Valve | Brass Stop Valve |

|---|---|---|

| Material | Plastic (PPR) | Brass (copper-zinc alloy) |

| Strength | Moderate | High |

| Corrosion Resistance | Excellent (non-metal) | Excellent (with proper surface treatment) |

| Installation | Heat fusion | Threaded or compression fitting |

| Temperature Range | Up to 95°C (203°F) | Up to 150°C (302°F) |

| Pressure Resistance | Moderate (PN16 max) | High (PN25-32 or more) |

| Typical Lifespan | 20-25 years (indoor use) | 30+ years |

| Cost | Lower | Higher |

| Applications | Residential water systems | Residential, commercial, industrial |

Deeper Insights:

1. Material Behavior

PPR can withstand most household water conditions, but it doesn’t like sunlight or physical stress. Brass, however, is tough. It resists both internal pressure and external force. That’s why brass stop valves are often used in outdoor, exposed, or high-pressure environments.

2. Installation Method

PPR valves use heat fusion, which bonds them permanently to PPR pipes. This makes them leak-proof — but only if installed correctly. Brass valves, on the other hand, are connected with threads or compression nuts. This makes them easier to replace or repair.

3. Certification and Reliability

One of my Canadian clients once told me he received PPR valves with fake WRAS marks. That ruined his trust in the supplier. Brass valves are often more strictly regulated, and it’s easier to trace the material quality. For commercial jobs that require paperwork, brass valves usually win.

4. Appearance and Trust

Believe it or not, buyers often trust metal over plastic, especially when selling to final consumers. Brass looks durable. It feels reliable in hand. If you're dealing with end customers who judge quality by look and feel, brass makes selling easier.

PPR stop valves work well in plastic piping systems with low to moderate pressure, but for strength, reliability, and versatility — brass stop valves still lead the way.

-

Learn about Polypropylene Random Copolymer's unique properties and why it's favored in plumbing applications. ↩